On this one-year anniversary of his passing on Feb. 27, 2013 (his wife Lorrie passing three days later on March 2 — both from cancer), I’m posting my eulogy of Wayne Maeda, who helped to shape the future of a painfully shy kid, and helped this kid validate his father’s wartime resistance, and eventually share that story with the world… Thanks Wayne.

At the opening of the Sacramento History Museum exhibit, “Continuing Traditions: Japanese Americans – Story of a People”

Eulogy: Remembering Wayne Maeda

By Kenji G. Taguma

March 8, 2013

I am deeply humbled to be before you today, to talk about my mentor, my longtime collaborator, the Nichi Bei Times and Nichi Bei Weekly’s longest contributing writer, my closest advisor, and mostly my dear friend, Wayne Maeda.

Wayne’s Story

You might be surprised to learn that Wayne wasn’t all that great of a student in high school — he didn’t want to study, and hated math. He initially took some business classes in college, thinking that he might help his dad’s construction business, but he declared Social Science as his major, graduating from CSUS in 1969 after spending two years at Sacramento City College.

His wife Lorrie conveyed, “He always called himself the accidental professor, because that was certainly never his goal.”

In the early days of Ethnic Studies, he was still a graduate student, teaching undergraduates near his own age. Back then, he ran down to other universities like UC Berkeley, UCLA and UC Davis to help get ideas to build the curriculum.

Around 1970-71, Wayne was the director of the Asian American segment of EOP, the Equal Opportunity Program on campus. He was in charge of about 40 to 50 peer advisors, who each were advising up to 10 students.

He received his MA in Social Science in the mid-1970s. As the Ethnic Studies Program pushed the CSUS Library to expand its collection, the Library hired Wayne to help add books. Ethnic Studies, Wayne recalled, “asserted political power to bring diversity to campus.” This included taking part in hiring faculty of color.

Wayne always sought out historical accuracy, no matter who challenged him. He sought to inspire, educate and make students reach their full potential.

Wayne the academic was always reading the latest, most up to date information, constantly educating himself.

But he was not without insecurities about his teaching. “I always thought I could have done a better job,” he said. “Maybe a better approach.” Until the end, he said he still had some insecurities about “not knowing enough.”

On Turning Waymad

So how did “Wayne Maeda” become “Waymad,” as his e-mail address suggests?

“I remember white kids calling us Japs,” Wayne told me, recalling grammar school experiences. “After you punch a few kids out, they pretty much left you alone.”

He remembers one incident at Sacramento City College, an Economics class where one professor told the Japanese American students “you aren’t going to get anything higher than a B.” This teacher, a veteran from the South, couldn’t tell the difference between Japanese from Japan and Japanese Americans.

Or maybe it was in junior high, when his teacher on December 7 would ask, “Mr. Maeda, what is today?” Being asked this on Pearl Harbor day made him feel “like the enemy,” he said. He was pissed.

Because of these experiences, it’s easy to see how historical accuracy and social justice became his calling card.

Perspectives

I’d like to take this time to share some perspectives of Wayne, taken from his book of “Thank You, Wayne” letters and personal comments people have made to me. He has been called at times “humble,” “generous,” “caring,” “funny,” “radical,” “prickly” and a “curmudgeon.” But there are many sides to Wayne.

To his eldest daughter Yumi, he was tough. “My father was very hard on me, but I know he always pushed me to be the best I could be,” she said. “I think he always pushed because he knew there was more I could do, more I could be. He himself never stopped learning or working, and this served as a great role model for me.”

Haruo Tamano, Wayne’s former teacher’s assistant in the early days at CSUS Asian American Studies, would become a lifelong fishing buddy, partaking in more than 400 fishing trips with Wayne over the years, including one adventure in Tomales Bay where Haruo wasn’t sure they would survive, given strong winds and a small boat.

In recent months, many have told me how they appreciated Wayne’s countless book reviews in the Nichi Bei Times and Nichi Bei Weekly over the years.

“I have benefitted tremendously from the many book reviews you have had published relative to Japanese American history, society and culture,” wrote Japanese American Studies Professor Art Hansen to Wayne. “In my opinion, you have been spot on in all of your reviews.”

UCLA Asian American Studies Professor Lane Hirabayashi said Wayne’s reviews kept him “on top of current publications.” “If you praised an author’s work, I always made note of it,” he said.

Paul Osaki, the executive director of the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California, remembers Wayne fondly. “Wayne was just one of those guys you could always go to when you needed help, advice or anything,” said Paul. “Wayne was also one of those guys who could get things done, didn’t like bullshit and never brought attention to himself.”

Others remembered his generosity.

“When my brother-in-law became paralyzed from waist down, Wayne promptly built a ramp at my mother-in-law’s house,” said Raymond Lee, who was an early student of Wayne’s at CSUS. “Whenever I bring up Wayne in conversation, my mother-in-law always tears up.”

Satsuki Ina recalled that Wayne would financially assist EOP students in buying books and other costs. “Students who had never been on a college campus, anxious, confused, fearful, and overwhelmed not only got help from Wayne, but really knew that he cared about them,” she said.

Longtime colleague Dr. Otis Scott called Wayne “the heart and soul of Asian American Studies,” who “remained a solid and intellectual force” within the Ethnic Studies Department and one of its “most respected teacher-scholars.”

Sacramento City College counselor Keith Muraki mentioned his high ratings on ratemyprofessor.com:

“I hated history until I took his class,” one student wrote. “He tells it how it is. I love this teacher. I recommend him to anyone, but you have to be willing to learn.”

“No BS with this guy,” another student wrote. “He minces no words… “

Congresswoman Doris Matsui called Wayne “one of Sacramento’s treasures” who was “loved by so many of us.” She thanked Wayne for his role in developing the Robert T. Matsui Legacy Project Website, a collection of audio and video clips, as well as documents and photographs of the late congressman.

Remembering Lorrie

But one of Wayne’s greatest accomplishments may have been finding love in his later years, with his “Wifey” Lorrie.

I believe that we should recognize Lorrie for her longtime collaborations with Wayne, first on the landmark 1992 Sacramento History Museum exhibit on the Japanese American experience. In our recent talks, Wayne called the exhibit his “greatest accomplishment,” and mentioned how one day with things in disarray, Lorrie came in to help organize a number of volunteers. She was good with people, and people responded to her.

Then, there’s Wayne’s book, “Changing Dreams and Treasured Memories: A Story of Japanese Americans in the Sacramento Region,” Wayne’s lasting legacy. Lorrie helped him put his seminal work together.

Andy Noguchi recently recalled another collaboration between Lorrie and Wayne, when they both served on the 2011 Florin JACL Manzanar Pilgrimage planning committee, which organized a tour of the wartime concentration camp.

“Wayne and Lorrie organized an Educators’ Project for that year,” Andy recalled. “They recruited, trained, and involved dozens of college professors, school teachers, and students for the three-day bus pilgrimage. We had a great trip with two tour buses and about 100 people, the most we’ve ever had. It wouldn’t have happened without Lorrie’s dedication, passion for history, and hard work with Wayne.”

The last half of 2011 was one of tragic proportions for Lorrie. Not only did Wayne discover his cancer, but Lorrie’s beloved son Matt died at age 38, and her brother in Virginia succumbed to Alzheimer’s. And, to end the year, Lorrie discovered that she herself had breast cancer.

Yet through it all, she would somehow find a way to stay positive, to find what she called her “butterflies and rainbows.”

Then, when his cancer returned late last year, Lorrie sent out e-mails to friends and colleagues soliciting “Thank You, Wayne” letters. She wanted to make sure that he knew that he was loved and respected, particularly as he reached his final days. Lorrie also wanted Wayne’s daughters to know more about how he had impacted so many people, across the country.

When Lorrie unexpectedly passed away last Saturday, it was tragic, but there’s also some underlying beauty in the way she left. She hung on long enough for her daughter Kristine to make the trek across the country from Tennessee, amidst numerous delays. And then, Lorrie quietly left us, to join her beloved Wayne, her son Matt and her brother Hal.

Letter to Wayne

Lastly, I wanted to share an excerpt of my letter to Wayne on Feb. 23. It’s a letter I’m sure that he never read, as he was too far gone by this point.

Dear Wayne,

It’s hard to imagine the mass transformation that I’ve made since wandering into your class more than 20 years ago. I wandered into your Asian American Studies class, probably on accident, still a painfully shy kid. To this day, I think I actually wanted to take an Asian Studies class, learning more about Asia. But this may have been the best “mistake” I may have made, because it led me to you, and to my destiny. And while I was “lost,” through you I would find my true calling. Through you, my eyes were truly opened, as I saw a fellow Sansei, albeit a bit older, who cared enough to document our community’s history.

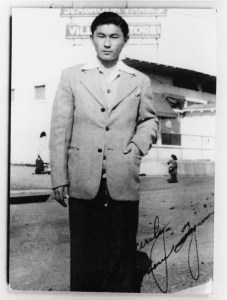

You were the greatest role model at the most crucial time for me. Not only did you help me understand the importance of my father’s wartime resistance, but you also validated his experience in the eyes of history, helping me to “connect the dots,” as you would say. For years, my father had complained that “no one knows about us guys. No one knows about us resisters.” Thanks to you, he started to get his ultimate vindication.

After taking your class, I went full steam ahead in changing my major to Ethnic Studies, and in becoming what I was told the most active student on campus. In just 1.5 years, under the Ethnic Studies Student Association, this once-shy country boy would go on to help organize some two dozen events or forums. I was even able to publish three editions of an Asian American newspaper on campus, the AsiAmerican Journal. None of this, however, would have happened if you had not touched me.

You quickly taught me what my life mission was to be, to make sure that our stories were documented, in an accurate manner. You, along with my father’s experience, helped to give me a voice that I never knew I had.

Over these past few months, you have given me tremendous access to your life, your thoughts, your insecurities, your accomplishments. I’m so very grateful that you had allowed me to conduct your oral history, and to spend some cherished moments with you and Lorrie, which taught me so much about love, strength and perseverance. I’m so glad that you’ve found each other, and that you’ve been able to share in such happiness, even throughout all your struggles. Lorrie is such a strong, amazing woman, and we’re all the more better people knowing and loving her.

Everything I’ve done, and will continue to do, is a testament to and in dedication to what you taught me. I want to thank you for the incredible example and legacy that you have given me, and for helping to vindicate my father in the eyes of history. You really saved me.

With deepest respect and gratitude,

Kenji

Final Message

In closing, I want to leave you with some challenges, in the spirit of Wayne. First, for those of us involved in documenting Japanese American history, we should do so with a fierce commitment to historical accuracy. We should NOT keep segments of our history marginalized, just because they don’t follow a popular or attractive narrative.

Second, for those of you in positions to lead, inspire or otherwise influence young people — whether you’re a community leader, educator, supervisor or even a parent — don’t be afraid to do so. They are, after all, our future. If someone younger reaches out to you for advice, don’t turn them away. You just never know what that young person will do someday, and what they will achieve.

Wayne, thank you for those many, many hours in your office, for serving as my mentor, and for taking a chance on me. I am determined to honor your legacy in everything I do.

Thank you.